On the surface, there’s nothing very funny about roadkill. The fact that millions of animals die on North American highways every year is a sad testimony to how our automobile addiction has harmed nature.

According to studies, an estimated 41 million squirrels die every year on U.S. roads alone. I’m told that as a kid I once came home from school sobbing because I’d seen a squirrel run over. None of us have enough tears in our bodies for the 26 million cats and 15 million raccoons that die every year on American roads.

And yet roadkill has become part of our pop culture. Google “roadkill” and you’ll get more than 1.5 million hits. There are entire websites devoted to roadkill cuisine, supposedly a hillbilly delicacy.

A 1990 Canadian movie called Roadkill (about a band on the road in northern Ontario) is something of a cult classic. The term “roadkill on the information superhighway” has been used in numerous books, articles and websites to describe those left behind by rapidly changing computer technology.

Even my late mother, who was a very creative person, used to gather bits of fur, feathers, porcupine quills or skulls from roadkill to incorporate into masks and other artistic creations.

So what does all this have to do with photography? Evidently a lot. A search on the photography website Flickr for groups about roadkill comes up with 163 hits. Granted some of those come up because their descriptions explicitly say that they are for animal pictures excluding roadkill, but apparently there are lots of people out there who enjoy shooting dead animals (with a camera, not a gun) and calling it art. My favourite group title is Cute Girls and Roadkill, even though its 23 members don’t seem to have been too active lately. I am not making this up. If I posted a picture of a woman to this group, she might rightly wonder if I saw her as a cute girl or as roadkill.

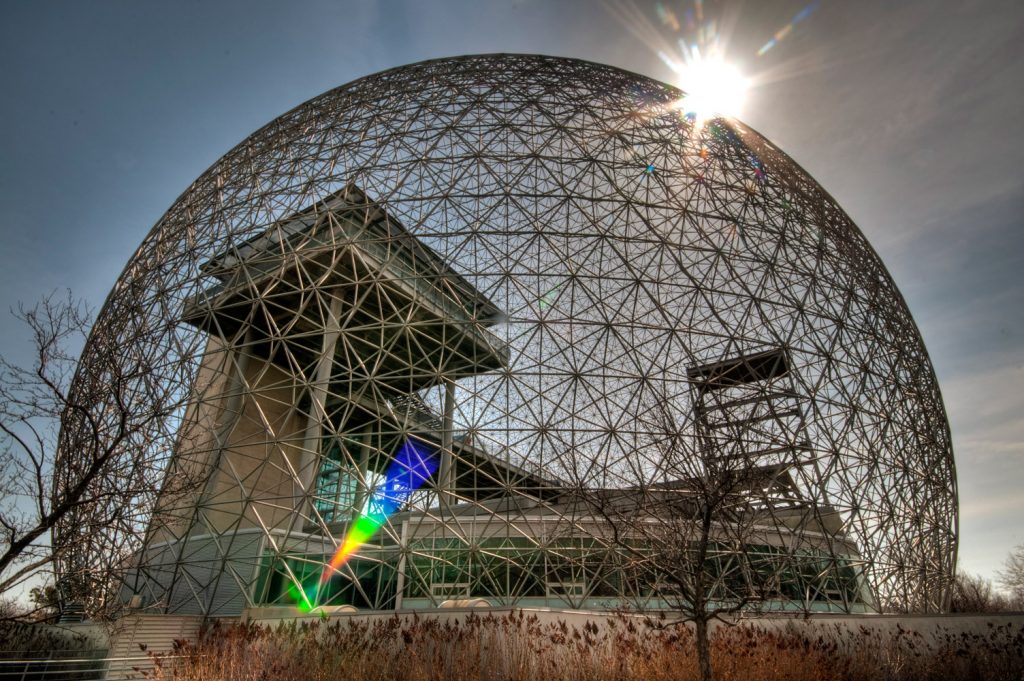

All this is leadup to a crazy photo idea I had last fall for a shot titled Photographer Roadkill. The idea was inspired when I looked at the photos of one of my Flickr contacts, PMck / Perry, an Ottawa-area photographer whose work I have watched blossom over the past year. Perry has an obsession with a particular bridge west of Ottawa that he refers to as “that bridge.” It’s the bridge on the old Highway 17 across the Mississippi River (not to be mistaken for its U.S. namesake). Perry filled his photostream with dozens of shots of this bridge from all angles and all times of night and day.

I began to worry about Perry. Quite aside from the fact that it’s not normal to be obsessed with a bridge, I worried that he might get so absorbed in photographing the bridge that he might not notice an oncoming car, and might end up as — roadkill. And what if other photographers shared Perry’s obsession and they also ended up as roadkill on THAT bridge? And then what if some of those photographers who shoot for Flickr groups about roadkill came by and saw Perry and the other photographers strewn across the highway and decided to take some shots? You can see where this is going.

At the same time, I’d been looking at the photos of another Flickr contact from Pittsburgh, Dave DiCello, who had been doing some interesting stuff compositing multiple shots of himself into a single photo. I particularly liked one of five versions of himself sitting around playing cards and drinking beer. So I got the idea of trying the same technique with multiple shots of myself as a photographer roadkill on that bridge. I would send it to Perry as a warning of what can happen if you’re not careful taking pictures on highways with fast-moving vehicles. I was even going to use a stuffed dog to represent Perry’s adorable standard poodle Cooper, who accompanies him on shoots.

I set up my tripod on THAT bridge, used the timer, and grabbed a couple shots of myself lying on the road. Trouble is, every time I got into position, I would hear a distant car approaching on the highway. I worried that I might end up as real photographer roadkill. Besides, the lighting was very harsh. So I abandoned the project after a few shots, and this is the best I got.

I thought of going back in better light and taking a friend to spot for cars, but then I thought better of the whole idea. It was all very, very sick, and I was sure that if I sent it to Perry he would be horribly offended. Especially placing a stuffed poodle on the road could have caused him to be extremely upset. Not everyone shares my sick sense of humour.

So, I forgot about the idea over the winter, and life carried on.

And then, about a week ago, I was looking at Perry’s photostream on Flickr, and was astonished to see he’d done a photo of his dog Cooper lying on the centre of the same road by the same bridge. And he’d titled it — you guessed it — “Road Kill.”

It turns out then, that I’m not the only one with a wacky, sick sense of humour. And Perry, who I’ve never met, except on the internet, shares some of my wackiness.

And roadkill can be funny, and can have a lot to do with photographers.