I’ve now been back in Canada for five days, four of those back in Osoyoos. I’ve still not adjusted to the radical change in time zones and the missed sleep, but I’ve slipped back right away into my regular work life.

It was definitely spring in Vancouver. The blossoms and magnolias were in full bloom. Here in Osoyoos it’s spring too, but the biting winds can feel chilly and it’s often dipping well below freezing at night.

In India, I saw the seasons change from spring to summer in the month I was there. By the time I left at the end of February, daytime temperatures were well into the 30s.

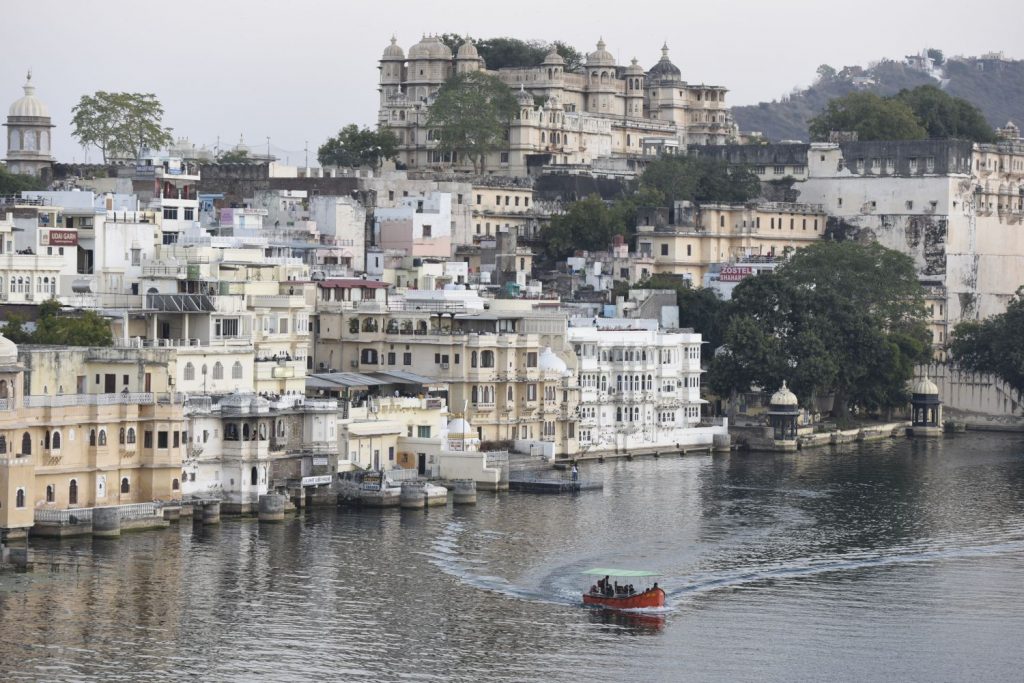

While in India, I often reflected on the major changes since I last visited in 1977. Some things were radically different, though much has stayed the same.

Technology is the biggest change. In the 1970s, there were of course no mobile phones and there were very few landlines. Today, everybody except for the poorest of poor beggars has a mobile.

Indians love their mobiles, and in any bus or on any train, there are dozens of conversations taking place simultaneously into mobile phones. Trains and train station waiting rooms have electrical outlets for people to charge their phones and they are constantly in use. Stores everywhere offer “recharges” or top-ups of pre-paid mobile plans.

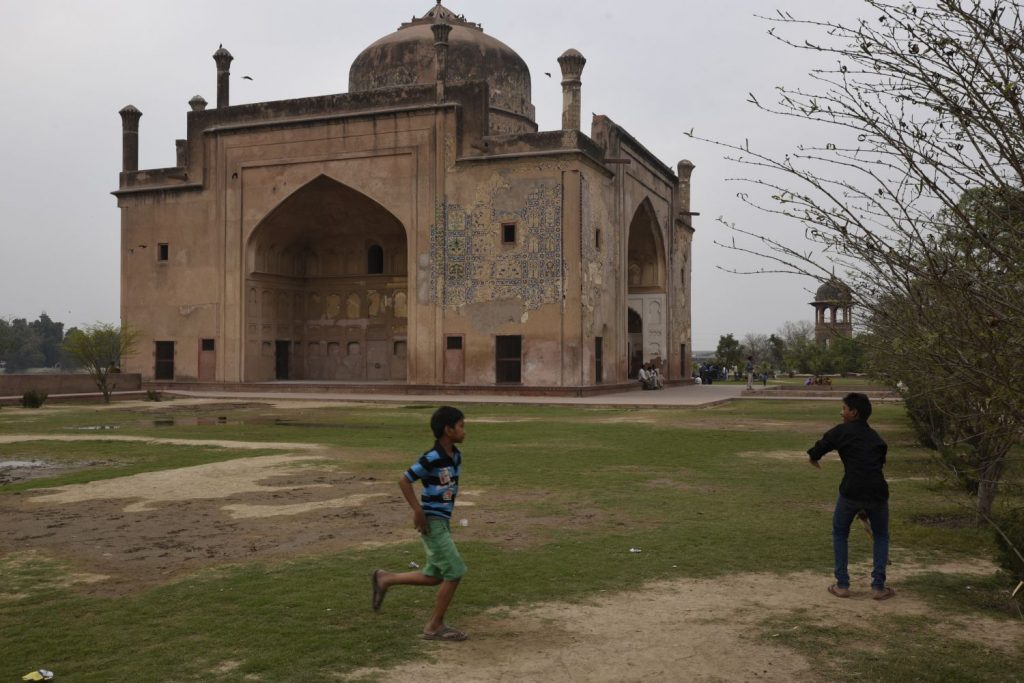

At any tourist attraction, Indian tourists spend much of their time posing for photos on mobile phones. Some bring telescoping sticks to hold their phones at a distance in order to take group “selfies.”

Traffic is another big change. In the 1970s, the bulk of traffic was bicycles. Sure there was the odd Ambassador car, often a taxi, and auto rickshaws, now called tuk-tuks, were fairly widespread. But today most traffic is motorized and it has grown exponentially. Especially the infernal motorcycles have taken over the streets – and the alleys and lanes usually built with pedestrians in mind.

Gone are the quaint-looking monstrosities of trucks that looked like they were thrown together with wooden boxes and then garishly painted. Today’s trucks look like trucks, even if they are more decorated than ones in the West.

In the 1970s, most trains were pulled by steam engines. Today, the majority are diesels and some are electric. I never saw a steam engine the entire time I was in India this time.

Hotels have changed. While really cheap hotels still exist, there are a lot more mid-range hotels offering such amenities as relatively clean rooms and bedding, hot water, televisions, wi-fi that sometimes even works and western-style toilets.

Prices have gone up accordingly. In the 1970s, a basic cheap hotel room might cost about $2 and a mid-range hotel might cost about $4 – $5. Today, a mid-range room costs between $20 and $40 and more in the big cities.

There are smaller changes. When you travelled by train in the 1970s, the chai sellers always came down the platform or the train cars calling: “Chai, chai, chaeeeeeee.” They either gave you a little earthenware cup that you smashed on the ground when you were finished, or they gave you a china cup which they returned for when you had finished.

Today, they usually give you a paper cup, or worse, a plastic one.

Plastic bags are much more common. I brought plastic bags with me, remembering that they were hard to come by. Today, however, they were everywhere and merchants gave them freely.

Transportation on the whole is easier today. The metro (subway) in Delhi quickly takes you around the city below the traffic jams. No longer are you dependent on collective auto rickshaws or individual ones.

No longer do you need to spend half a day trying to buy train tickets. Today, you can easily do it online or you can buy through independent agents relatively easily for a small fee. Even when you have to buy tickets at the station, the process is easier.

Likewise, you no longer have to spend a couple hours at a bank trying to exchange travellers’ cheques. Today, there are many ATMs and many of them accept foreign credit and debit cards, dispensing the money in rupees.

In the 1970s, drinking water was often suspect. One of the cheapest things you could buy was a glass of cooled water from a street vendor for 5 paisa, or a 20th of a rupee. Today, safe bottled water is easily available at either 15 or 20 rupees a litre.

Which brings me to the purchasing power of the rupee. In the 1970s, the rupee was worth between 10 and 13 cents. Today it’s worth just 2 cents Canadian, and even less in American cents.

Of course the value of the dollar has also changed, so it’s best to compare what a rupee will buy.

In the 1970s, the standard price for chai was 25 paisa, a quarter of a rupee, or as they called it then, char anna, or four annas. Today a very small cup is 5 rupees while a standard one is 10 rupees.

You could get a standard thali meal in those days for 1.50 to 2.50 rupees. Today it’s more like 70 to 200 rupees.

It seemed to me that English was less used today than 38 years ago, perhaps because the British Raj has faded more into history. But it might just be where I was travelling. I spent more time in the north, where people tend to use Hindi as a lingua franca. Last time, I was more in the south where people often use English when communicating between people from different states with different languages.

I met a few people who spoke English very well, but most had none at all or spoke only a very basic English. My efforts to learn Hindi before my trip definitely paid off, perhaps not in profound conversations, but at least in good will.

When I visited India in 1977, the government was throwing Coca Cola out of the country and promoting Indian-made soft drinks. Many markets had locally made and bottled soft drink concoctions of uncertain quality.

Today, Coke and Pepsi definitely rule and both companies sell everything from cola to bottled water and even fruit drinks like Maaza, a sweet drink made with real mango pulp and bottled by Coca Cola, or Limca, a lemon drink from Coca Cola.

Of course some things about India have not changed or have changed only slightly and a lot of these include minor and major annoyances.

No change for larger bills: Nobody wants to give up change and people always claim to have none. Yet bank machines issue money in 500 rupee notes that few people accept except for larger purchases like hotel rooms. You are constantly trying to devise strategies to get change from larger notes in order to pay exact change to rickshaw drivers and others who insist they have no change.

Even at the ticket window of the main entrance to the Taj Mahal a few minutes after opening they claimed not to have 250 rupees change for two 500 notes to pay the 750 foreigner admission price.

India is still very much a cash economy, but few businesses have cash floats.

Garbage is everywhere: You do find some more garbage bins than I remembered in the 1970s, but they are still rare and many people don’t use them. Once I bought a drink and asked the seller what I should do with the bottle when finished. He pointed to the ground outside his stand indicating I should just throw the bottle there. With more plastic and packaging, the garbage has become worse than in the 1970s when things were often wrapped in biodegradable wrapping like banana leaves.

Animals on roads: You no longer see cows on the streets of Delhi, but you see them everywhere else. And dogs, monkeys, goats, sheep etc. In some places they pose a risk to drivers, but usually they are more a risk to themselves.

Dealing with rickshaw drivers: In the 1970s, a lot more of the rickshaws were cycle rickshaws. These still exist, more in some places than others, but increasingly they’ve been supplanted by auto rickshaws or tuk-tuks as they’re now called. Either way, many drivers will try to cheat foreigners (and even Indians) as a matter of course. When you exit a train, they pounce on you like a swarm of mosquitoes. The more aggressive ones are the worst for trying to charge inflated prices, so I often bypassed these touts and went straight to some guy quietly waiting with his tuk-tuk.

That’s not to say that all are cheats, and I had some who seemed to be very honest. In one case, I had a driver who asked a very fair price and went straight to my destination without trying to push me into shopping. I was so grateful that I offered him a tip, which he refused. This, however, only happened once.

Horking and spitting: The sound of loud throat clearing, horking and spitting is by no means unique to India, but it is very common and still sounds disgusting. Often now you see signs telling people not to spit, though I don’t know if these do any good. One thing I saw a lot less of was the spitting of bloody red paan juice from concoctions that many Indian men chew. Is paan perhaps less popular than it was?

Coffee: India is a tea country and good coffee is hard to come by. Coffee is more available now in the north than it was, but almost always, except in some more expensive places catering to tourists, it’s Nescafe. Although I normally drink coffee black, I took to adding milk and sugar to hide the disgusting taste of the Nescafe.

Questions from strangers: As a rule of thumb, if an Indian comes up to you and starts a conversation, they want something from you. The more satisfying interactions usually came when I initiated the contact. Of course, many people do approach you innocently, but it’s hard to know because the questions asked by a tout and someone who is just curious about you are often the same: What is your country? What is your name? First time in India?

I tried to be patient and to give most people the benefit of the doubt unless they were obviously touts, but I did tend to be a bit guarded when strangers approached me to ask questions.

Traffic: I sometimes saw zebra crosswalks, but in India they have no meaning whatsoever. Cars never stop for pedestrians except very occasionally if it looks like a collision is otherwise unavoidable. You take your life in your hands when you cross the street. I often put myself in the middle of a group of Indians when crossing, and I always planned my crossing with a few escape routes, typically crossing at places where there is an island in the roadway.

You always have to look in both directions because vehicles, especially infernal motorcycles, often drive on the wrong side of the street and in the wrong direction. People ignore traffic lights, one-way streets and virtually any traffic signs and signals.

On highways and city streets, people are constantly passing and often crossing into the oncoming traffic to do so. There is a constant sound of horns honking. Horns have a different meaning in India. In North America, they usually mean something to the effect of: “Wake up, asshole.” In India, they just mean, “I’m here. Watch out for me.”

Postscript: When I was in Ujjain, I copied a memory card from my camera onto a USB memory stick at an internet café, but the computer I used had a virus, and I lost access to all the photos taken over two days.

Back home, I located software to recover the photos from the USB drive and have successfully salvaged them. I’ll post some of those photos to the Bhopal and Ujjain blog entries shortly when time permits.