Trying to lose weight – packing for an adventure from Richard McGuire on Vimeo.

Trying to lose weight – packing for an adventure from Richard McGuire on Vimeo.

It was exactly 10 years ago today that my mother, Joan McGuire, died on her 79th birthday.

I had a ticket from Ottawa to Halifax on the earliest flight that day and then a long drive to Cape Breton where she had been living with my sister, Sandra. I knew she was near the end, but I phoned when I got out of Halifax and my sisters gave me the sad news that she’d died in the early morning hours.

When I got there, the family gathered in the room where my mother still lay in bed. She had left an envelope that was not to be opened until after her death.

She loved poetry and nature, among so many other things. Inside the envelope was a poem she’d written. It fell to me to read it. I managed to keep my composure that time, I think because I was still in shock, but there wasn’t a dry eye in the room.

When I go

I leave for you

these things I’ve loved —

Sunlight dancing on a summer lake,

or shattering crystal through winter spruce on a diamond-glitter ski-swooshing day.

Haunting cries of wild geese returning, or departing.

Smell of new-mown hay.

Late summer meadows lit by goldenrod and asters… Wind singing through pines, or setting aspen leaves atremble. Salt-spray lashing faces by darkening wrathful seas,

and, with luck, a piper playing

somewhere, afar in a fog.

Stories and laughter round a winter fire. Beowulf, and blood-red wine.

I have loved these, and more.

And when I say goodbye for the last time, I’m not really gone

as long as I leave you

these things I’ve loved.

But above all I leave for you always

my love

I only had a few hours to explore the historic centre of Morelia on Sunday.

Morelia is the capital of the state of Michoacán and it’s now a city of close to one million people. But its historic centre displays a strong Spanish influence with decorative buildings of stone.

In fact, before the city was renamed to honour independence leader Jose Maria Morelos, it was named Valladolid after the Spanish city.

I left early from Patzcuaro and got a bus to Morelia, leaving too early to find any breakfast places open. So, I ended up eating breakfast on the main square of Morelia at outdoors under one of the portales or colonnades.

After, I explored on foot, popping my head into the impressive cathedral, where a Sunday service was taking place.

The main street in the historic centre was closed to vehicle traffic so it could be used solely by cyclists and rollerbladers. I gather this takes place every Sunday.

I’ve seen other cities in Canada do this, but never on such an impressive street.

My flight to Tijuana didn’t leave until 4 p.m., but I returned to the bus depot, where I’d left my baggage, in good time to catch another taxi to the airport.

The driver who took me from downtown to the bus depot was interested in hearing what I had to say about Donald Trump. I assured him I was not from the United States, and that Canadians would have solidly voted against him if he were running in our country. (I didn’t tell him that a recent poll showed a majority of Albertans actually would support Trump).

Needless to say, the driver was solidly opposed to Trump, as are many Mexicans who have ever worked in the U.S. or have family there.

The plane was full for the three-and-a-half-hour flight to Tijuana and as so often occurs there were screeching babies strategically placed around the cabin for in-flight entertainment. Have I mentioned I hate planes?

My driver from the airport to my hotel in Tijuana was one of only about four Mexicans I’ve met this trip who spoke English well enough to converse in it.

He was also not impressed by Trump. He had worked in San Diego and two of his children were born in the United States, giving them U.S. citizenship.

I’m staying at Hotel Caesar’s, which is said to be where Caesar’s salad was invented. Only the façade hints at its history as a place where the rich and famous stayed in the mid-20th century when Tijuana was a destination for sin.

It’s right on Avenida de la Revolucion, or La Revo as it’s known, which is where all the loud bars and such are located. The area actually seemed surprisingly tame from how I remembered it many years ago, and there was heavy police presence.

I’m very disappointed that I haven’t yet seen any donkeys painted with stripes to look like zebras, as Tijuana is known for.

Today I’ll cross the border at the pedestrian crossing to San Ysidro. I fly from San Diego to Vancouver via Los Angeles later this afternoon, arriving late tonight.

Isla Janitzio on Lago de Patzcuaro is a bit of a paradox.

From the distance, as you approach it by boat, it’s an attractive conical island out in the lake a few kilometres north of Patzcuaro.

The lake is ringed by mountains. It seems like a lovely spot.

But as you look closely at the water, you see that it’s a muddy brown. In fact, the lake is quite polluted.

And as you get close to Isla Janitzio, you see that it is crowned with a stone monstrosity at its peak. It is the ugliest statue of independence leader José Maria Morelos in all of Mexico.

Isla Janitzio is known for having one of the liveliest Day of the Dead festivals, but outside of that one time of year, it is simply a big tourist trap. Although I did hear two people talking in what sounded like American English, the vast majority of visitors were Mexican tourists.

As you approach the island, “fisherman” in canoe-like boats begin casting butterfly nets. A short while later, one of them paddles over to the tour boat, grabs a hold of it, and starts asking people for tips. Apparently, this kind of net fishing is no longer economical, but it does make an interesting tourist attraction.

When you step ashore, you are met with hundreds of vendors selling trashy souvenirs, refreshments, or fried fish, apparently from the polluted lake.

Thankfully, there are no vehicles on Isla Janitzio. Instead of roads, there are just long, twisty walkways up numerous stairs, past more and more souvenir stands and fish restaurants.

At the top of the climb, of course, is the ugly statue of Morelos. After buying a ticket, you go through turnstile and then you can climb into his belly. A narrow walkway with a low railing spirals up higher and higher, lined by murals depicting his life.

If you make it to the top, you can get a view from inside the wrist of his raised right hand.

I could handle the height by itself without suffering vertigo, but what got to me was the crowds of people trying to squeeze past in both directions on this narrow catwalk. So, while I made it to the top of his belly, I had had enough before I got into his wrist.

Often when I am in a foreign country, I enjoy visiting the attractions that local tourists visit because they say something about the culture, and it is fun to observe people enjoying themselves.

I loved Xochimilco, the canals filled with colourful boats near Mexico City, which I have visited on other trips, for example.

I even enjoy kitsch sometimes in the right dose. Places like Niagara Falls or Las Vegas can be fun for their extreme kitschiness. But Isla Janitzio makes even Niagara Falls look like a paragon of good taste.

I was glad I made the trip so that I could see it, but my regret was that I didn’t have the time to visit some of the villages that ring the lake and are probably much more genuine, while offering similar scenery.

I got a late start today, because I spent the first part of the morning getting organized for my trip home.

Tomorrow I’ll leave Patzcuaro early, and catch a bus to Morelia. Then if time allows, I’d like to spend a couple of hours in the centre of this Spanish colonial city, that resembles a city in Spain.

I’ll need to get to the airport in time to catch a late afternoon flight to Tijuana for my last night in Mexico.

(Below see more shots of Isla Janitzio as well as more from Patzcuaro)

I loved Patzcuaro when I first visited it in 2003. It’s a small city in the Mexican state of Michoacán that dates back to pre-Columbian times, at least 150 years before the arrival of the Spaniards.

While some neighbouring towns destroyed their character when they tore down the classic buildings and put up modern monstrosities, Patzcuaro couldn’t afford to do this, so it kept its historic centre.

It has probably slightly more than 80,000 people, and most of the historic area is within easy walking distance of its two main squares.

The largest square, Plaza Vasco de Quiroga, is known as Plaza Grande, because it is the larger of the two. The smaller one, Plaza Chica, is officially known as Plaza Gertrudis Bocanegra.

Quiroga was an enlightened bishop who was sent in to calm things down after a period of particularly brutal Spanish atrocities against the indigenous population. He cared for the well-being of the local people. Adopting the views based on the Sir Thomas More book Utopia, he encouraged the indigenous villages to become self-sufficient by developing craft industries.

Gertrudis Bocanegra was a local supporter of independence from Spain who was shot by firing squad during the struggle for independence in the early 1800s.

Much of Patzcuaro is made up of two-storey white buildings with tiled roofs, and the lower five feet of the buildings are painted blood red.

There are large portales or colonnades on the buildings around the squares, and many of them have restaurants, cafés and hotels beneath. Both squares have greenery, statues of their two heroes, fountains, and lots of pigeons.

Many of the hotels are in former 17th and 18th century religious buildings, mine included. My room has adobe walls, a 12-foot ceiling, with wooden beams on top. There’s a small balcony overlooking a street below, and at the end of the street to the right is Plaza Chica.

My room has a cross over the bed and the room is dedicated to Mater Dolorosa, or Our Lady of Sorrows.

Yesterday actually turned out to be my longest day of riding buses. Although the distance may have been shorter than my trip to Angangueo, it took longer because I was entirely on second-class buses that stopped everywhere to pick people up or drop them off along the road.

I left in the morning from Angangueo without any breakfast and rode a small bus, more of a large van, to Zitacuaro. Then I took the longer of the trips, well over three hours, to Morelia, the capital of the state. Finally, there was a one-hour bus trip to Patzcuaro.

As I watched the scenery go by, I noticed two things at the sides of the roads. First there were crosses indicating motor fatalities at a rate of sometimes two or three per kilometre. Secondly, between each of these crosses, there was litter everywhere. Evidently highway cleanup is a low priority in Mexico.

I spent much of today just wandering through Patzcuaro’s interesting streets. I did visit the market, and the public library which is in an old church on Plaza Chica and has an amazing Juan O’Gorman mural on its back wall showing in the history of Michoacán.

This will be my second night in Patzcuaro, and I’ll be staying here tomorrow night as well, before beginning my return home. Tomorrow I plan to visit the lake just north of here and some of the villages surrounding it.

The small town of Angangueo sits high in the Sierra Madre at the eastern edge of the state of Michoacán.

It’s small with a population of just under 5,000 people, roughly the size of Osoyoos in the off-season. The population has fallen greatly since previous decades when the town was known for its silver mining.

Today tourists come here to see one of the natural wonders of the world unfold – the migration of the monarch butterfly.

Every winter, millions of monarch butterflies arrive here to spend their winters on a few mountains in the immediate area. Conditions are perfect for them because the cool temperatures allow them to conserve energy through the winter, and there is the right amount of moisture for them.

It takes several generations of butterfly to complete one year’s migration, yet guided by instinct and their antennae, they know exactly where to return to each winter.

Normally the lifecycle of a monarch butterfly is four to five weeks, and that’s how long they live when they are born in Texas and travel north to Ontario and Québec.

But then, a super generation is born in Canada that actually lives up to seven months and this single butterfly makes the entire migration from Canada to Mexico. Riding the air currents high above the ground, they can travel more than 100 km a day on their migration south.

The phenomenon of their migration was only ultimately proven in the 1970s by a Canadian, Dr. Fred Urquhart, who dedicated 40 years of his life to unraveling the mystery of where the butterflies went in the winter.

Hundreds of volunteers in Canada and the United States put tiny identification stickers onto butterflies, and Urquhart tracked their movements. Finally, in his 70s, he came to this area and was amazed to find among millions of butterflies one that had a sticker that had been put on it in Minnesota, proving that a single butterfly had made the entire migration.

I arrived in Angangueo yesterday afternoon, and made arrangements with a local guide to take me up to El Rosario entrance to the sanctuary.

My guide, German (the Spanish form of Herman, not the nationality), has been guiding people to the sanctuary for about 30 years, and knows a lot about monarchs and their migration. He only spoke a tiny bit of English, so we communicated in Spanish. Our communication wasn’t perfect, but for the most part I understood his sometimes-complex explanations of this phenomenon. After a week in Mexico, my Spanish is coming back quite well.

For the trip into the sanctuary itself, you must use one of the guides provided, and they are there primarily to ensure that you don’t damage the butterflies or get lost on the way. My guide, Brianda, was a friendly young woman who spoke no English, but I found her even easier to understand than German.

The elevation of the sanctuary is around 3,000 metres or roughly 10,000 feet, so the air is quite thin. Although I have been at moderately high elevations since Guanajuato, I haven’t been at 3,000 metres recently, and so I was not well acclimatized. So, the ascent was somewhat difficult and I had to take frequent rests.

As I said to Brianda, she is a youth from the mountains and I am an old man from the lowlands.

The trail got easier, and we entered a meadow where the sun was starting to cast its beams over the vegetation. We started seeing butterflies, both flying in the air and drying themselves out on the ground.

A little higher and through the forest of a type of fir tree, Brianda pointed up to some branches that appeared to be weighted down. Looking closely, I could see that they were completely covered in monarchs, which were well camouflaged.

Where there were branches in the sunlight, many butterflies were fluttering through the air. It was an incredible sight, though I understand that in December and January, they are much more plentiful, and the sound of their wings can actually be quite loud.

I had to watch where I walked to avoid stepping on them. In the peak season, they cover roadways.

It was difficult to photograph them with the lenses I had and once again I craved a 600-mm lens, though I wouldn’t have wanted to carry it up that trail.

It was much easier coming down, and I met up again with German who had been waiting for me. He took me on a short detour to a lookout point over Angangueo on the way back, where I could look out over the rolling hills and mountains, the farm fields, and the town below.

At this point, many butterflies had descended in the warm sun, and they were flying all around. I even saw many back in the town, although the town also is full of wasps.

The temperature here is moderately warm in the day, about 18°C, but at night it falls to about 5°C, and there is no heating. Thankfully my hotel does provide warm blankets, but I still sleep with clothes and a jacket on.

Tomorrow morning I leave for the colonial and heavily indigenous city of Patzcuaro, which I last visited in 2003. I plan to spend three nights there before beginning my return home.

When I left my hotel in Dolores Hidalgo on Sunday, my plan was to catch a taxi to the cemetery to see the grave of ranchera singer/songwriter Jose Alfredo Jimenez that is shaped like a giant sombrero, and take the same taxi to the bus station.

When I stepped out of the hotel however, the street was filled with a large parade and crowds of people. I had completely forgotten that November 20 is the day the anniversary of the Mexican Revolution is celebrated.

The revolution started in 1910 after decades of rule by dictator Porfirio Diaz. He modernized Mexico, built networks of railways and made the trains run on time. But he also had striking workers shot, and he facilitated the seizure of land from indigenous peasants by his rich buddies. He used to powder his face white to hide the indigenous part of his ancestry, and he admired all things French. Every few years he held a rigged election to give the appearance of legitimacy. Finally, after the 1910 election, the people had enough and subsequently Don Porfirio fled to exile in France.

Historians argue about what the revolution actually accomplished other than leading to decades of one-party rule by the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional). My immediate concern though was getting a taxi.

The man at the front desk thought it might be difficult to find a taxi, but that is an understatement. He told me where there is a taxi stand if I could get across the parade route.

Unlike small-town parades in Canada, this one had gymnasts performing, marching bands and other entertainment, but I did not see any floats.

I managed to make it to the taxi stand after asking a policewoman for advice – she pointed me to an area where I could cross the parade discreetly. But there was only one taxi at the stand and no driver. I was told there was no other stand nearby and there were so many people in the downtown anyway that probably no taxi driver in his right mind would go there.

I decided my only option was to walk about 30 minutes carrying my much too heavy baggage to where I believed the bus station was supposed to be. It was where Google Maps put it, and the man at the front desk had confirmed it was.

As I got close to where it should be, I stopped for a refreshing drink and asked the woman if the bus station was indeed there. She told me it moved and the new location was at least 15 blocks away.

I double checked with another man in the area and got the same story. He told me it was very far and suggested that I take the city bus that fortunately ran directly from where I was to within a block of the bus station.

It was good advice and the trip was only five pesos or 35 cents.

I got a bus without difficulty to San Miguel de Allende, but then faced the same problem. The bus station is far from the centre and the few taxis that came by were always grabbed first by Mexicans, even though I had waited longer.

Finally, a taxi driver stopped, but when I told him my destination, he said it was impossible because there is too much traffic in the city centre. I pleaded and told him he could just get me as close as it was possible and I would walk the rest of the way. He reluctantly agreed.

When we got into the old city, I could see he was absolutely right. The little narrow cobbled streets were jam packed with parked vehicles, strolling pedestrians and vehicles stopped on the road unable to move in all the traffic. My driver cut through several smaller streets, constantly trying to find a way through, sometimes backing up and turning around.

At one time, we were heading straight into traffic on a narrow street, dodging to the side to let oncoming vehicles pass. I asked the driver, knowing the answer, if the road we were on was a two-way street.

“No,” he responded, smiling. “Es mi modo.” (It’s my way).

As we reached the end of it, there was a policeman directing traffic, and he just waved us through. The driver gave a small victory cheer, relieved that he wasn’t ticketed.

Finally, he turned down another narrow, cobbled street and pulled up at the front door of my hotel. No need to walk. It’s not customary in Mexico to tip taxi drivers, but I made an exception in his case.

After checking in and catching my breath, I decided to walk to the city centre, down the hill to check out the festivities. The central square was packed with people. There were mariachis playing music, women were wearing crowns of dried flowers, and in every direction people were taking “selfies” on their phones.

San Miguel de Allende is a colonial city that has been protected as a heritage site for many years. It’s not an over-the-top restoration as I’ve seen in some places, but without this protection I doubt it would have retained its charm.

The tall parish church that dominates the central square is pinkish stone and is compared to a wedding cake. The story is that the design was based on a postcard of the church in Belgium, and the designer, a stonemason, drew the design into the sand.

Some of the buildings to the edge of the square had stone arched colonnades over the sidewalk, as is typical in Spanish colonial design.

I had limited time in San Miguel as I had to reduce my stay from two nights to one. That’s because my next destination is the Monarch butterfly sanctuary in Michoacán, and the only way to get there practically was to leave from the neighboring city of Celaya in the very early morning.

So, I spent the Sunday afternoon and Monday morning exploring the streets of San Miguel and then caught a bus to Celaya where I set my alarm for 5 a.m.

The next day, Tuesday, today, was the longest I will be travelling by bus and was also the trickiest in terms of timing of connections. Fortunately, it went smoothly, though I almost missed the long-distance bus from Celaya to Zitacuaro, when the driver decided to leave 15 minutes early.

Fortunately, I spotted him getting onto the bus and went over to confirm it was the right bus. He didn’t have me on his list, but I had a ticket that I’d bought in advance. The first-class bus was virtually empty and even had functioning Wi-Fi on board.

Lastly, I caught a very non-first class bus to the town of Angangueo from where I plan to visit the butterfly sanctuary tomorrow.

It was a sermon, or perhaps more accurately a “cry” from Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla in Dolores on Sept. 16, 1810 that kicked off the struggle of more than a decade for Mexican independence.

His message was “Death to the gachupines” — a derogatory word for the Spanish-born class that ruled colonial New Spain.

Hidalgo was something of a renegade priest. He’d been exiled to Dolores because of his rebellious nature – he read banned books, kept a mistress and dared to believe that Christianity meant helping those less fortunate.

As noted in my account on Guanajuato, Hidalgo was subsequently captured in Chihuahua less than a year after launching the struggle for independence. His head was put on display along with heads of other independence leaders in Guanajuato.

The church where he launched the uprising is in the town’s central plaza. It’s a destination of pilgrimage on Mexico’s Independence Day, celebrated on the Sept. 16 anniversary of his Grito (cry) of Dolores.

Aside from that, Dolores Hidalgo, as it was renamed after independence, isn’t a major tourist destination.

But along with being known as the “cuna de independencia”, (cradle of independence), the city of 60,000 is also known as the birthplace of The King.

Of course, The King in this case isn’t Elvis, but rather is Jose Alfredo Jimenez, el Rey (king) of ranchera music. He lived his childhood here until economic circumstances (his father’s death, the Depression) forced his family to move to Mexico City.

Close to the end of this short life of 47 years in 1973, he announced at a performance that he wanted to be buried in his hometown of Dolores Hidalgo. His wish was respected, and he is now buried under a grave made to look like a giant sombrero.

As with many musicians, it was substance abuse – alcohol – that killed him. He died of cirrhosis of the liver.

He is said not to have been able to play any instrument, or to read or write music notation, but he had a powerful voice and was a talented lyricist. Many of his 1,000 songs have been widely covered by well-known singers, and his repertoire is at the heart of mariachi music. He’s a Mexican icon.

It’s often said that Jose Alfredo was a man who loved love and converted it to song. His lyrics are extremely sentimental and romantic, probably over the top and syrupy for an audience in Canada or the U.S. But they were well written and appealed to a broad spectrum of the Mexican public and beyond.

Often his mushy sentiments were written to the woman who became his wife, Paloma. Nonetheless his declarations of undying love only lasted until he began womanizing while touring.

His childhood home is now a museum of his life, and is well done. It’s a mix of memorabilia, photographs, video, and recordings of his music. Although I’m not bad at reading Spanish, this is one of a minority of museums with side-by-side English translation.

Dolores yesterday was quite chilly. I think the high was about 13, but it fell into the high single digits at night. Warm by Canadian standards, but keep in mind that Mexican buildings rarely have heating. I wore my clothes and a jacket to bed.

Sometimes in travelling, you stumble upon an event by serendipity. That happened last night when I discovered a festival of traditional dance was taking place in the main square on a stage facing Father Hidalgo’s church.

There were dancers in traditional styles from all over Mexico, some older and a number of children, though most were youths.

For the finale, they featured a local theme, complete with dresses with imagery of the two icons of Dolores – Father Hidalgo and Jose Alfredo Jimenez.

Today I’m off to San Miguel de Allende, where I expect to see many more gringos. It’s a major destination for American and Canadian expatriates, especially of retirement age. It’s also one of Mexico’s most beautiful colonial cities.

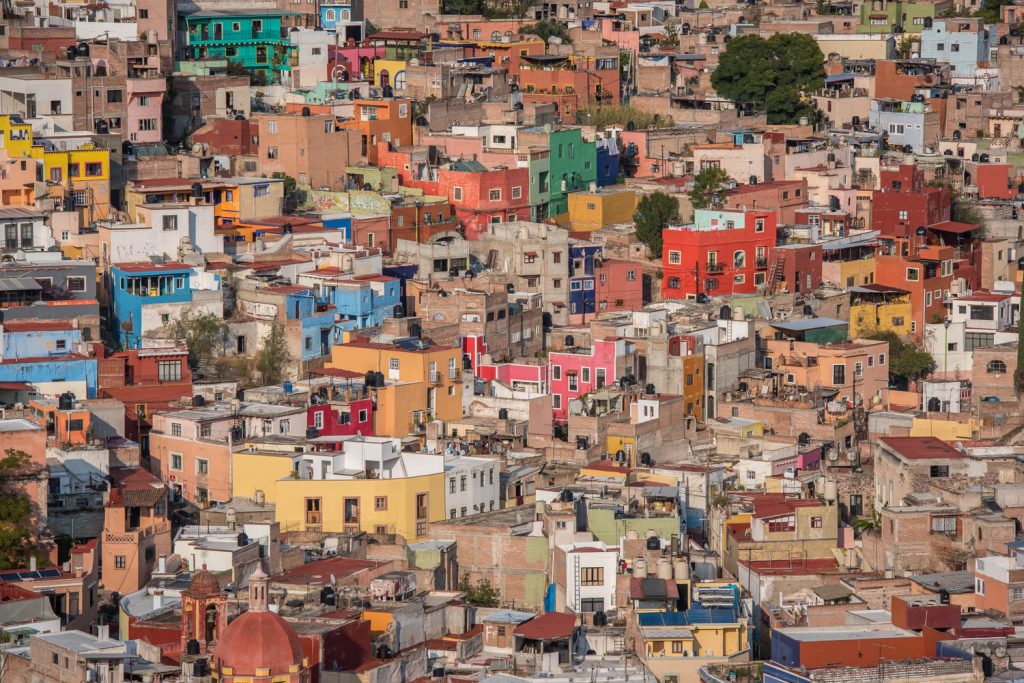

One of the posters for a tour of Guanajuato is headed “Un museo llamado Guanajuato” (A museum called Guanajuato).

It’s an apt description for this city of nearly 200,000 people that is the capital of the state with the same name. Here is found the history of Mexico’s Spanish colonial period and later its struggle in the decade following 1810 for independence from Spain.

Although I did see gringo tourists in the city centre, most of the tourists who come here are Mexican. Most gringos prefer Mexico’s beach resorts. But, despite being a showcase of history, Guanajuato is very much a real city that carries on with life, often oblivious to the visitors who come here.

Guanajuato was built on the massive wealth generated by silver mining, especially in the 18th century. Many of its ornate churches and fine colonial buildings date back to that period.

The city has preserved its character by maintaining tight control over building construction, signage and lighting. There are no loud store signs or brilliant neon, and traffic lights are very rare.

It’s a pedestrian friendly city in the historic centre. Many streets and alleys are pedestrian only, and others are closed to traffic when the evening festivities begin. The streets are narrow, winding and cobbled. Sometimes sidewalks are very narrow, meaning you must step onto the road when you meet another pedestrian.

A network of old underground tunnels carries traffic below the city, also helping to take traffic off the downtown streets. Some of these tunnels are in an underground river bed.

The city is built on the sides of low mountains, which limit its growth and means you’re often walking up and down, sometimes on alleys that wind up steep slopes with multiple stairways.

The city was the scene of the uprising that led to the war of independence in the early 1800s. High on the wall of the Alhondiga – then a granary, later a prison and now a museum – you can see the hook where the head of rebel leader Father Miguel Hidalgo was hung as a warning to the people.

The city is overlooked by an imposing statue of El Pipila, a poor miner, who strapped a flat stone to his back for protection and set the wooden doors of the Alhondiga aflame, enabling the rebels to capture it.

You can climb the steep stairs on winding alleys to reach the statue – which I did the first time – or take a funicular, which I did on a subsequent visit.

From there, you can look out over the city of Guanjuato, built on the rolling hills and low mountains, as the sun sets and the city lights up.

Much of my time in Guanajuato I spent exploring the streets or watching the constantly unfolding drama in the city centre at nightfall. I did visit several attractions, including the ornate Teatro Juarez, a theatre built in the late 19th century, as well as the Diego Riveira Museum, at the house where the great muralist was born and spent his first six years.

There is so much to explore here, but my time is limited. Today I leave for Dolores Hidalgo, the small city where Father Hidalgo kicked off the War of Independence with his “Grito de Dolores” (Cry of Dolores), a speech urging residents to rise up against Spanish rule.

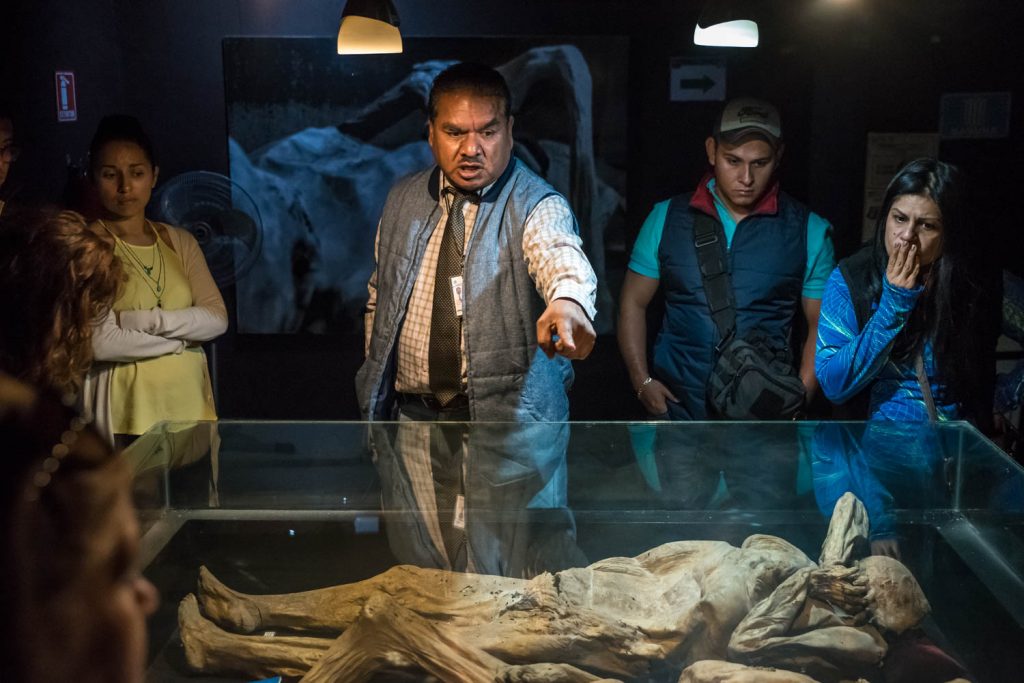

Today I looked death in the face – literally.

Let me first explain that Mexican culture treats death very differently – on so many layers.

One of the biggest events of the year is Day of the Dead (Dia de Muertos) at the start of November when death is celebrated. It’s a time for families to come together and celebrate their relatives who have died, but it also has traditions that go far beyond Halloween.

The calavera – literally skull, but often a decorative one – is a major icon of Mexico. Walking around Guanajuato, I sometimes saw people with a calavera on their shirts, much like some people wear Che Guevara, or especially in Mexico, Frida Kahlo.

Perhaps the best known calavera is La Catrina, a skull wearing an elegant lady’s hat. More on her later.

All this is to introduce the Museo de las Momias, or Mummy Museum, which I visited this morning. It’s a popular attraction, mainly for Mexican tourists, but I suspect a similar museum in Canada or the United States would be quite controversial and would probably cause outrage. As I said, attitudes about death are different in Mexican culture.

Long before the museum was established, dead people in Guanajuato were placed mainly in above-ground crypts. In the dry atmosphere, their bodies were mummified.

When the cemetery ran out of space, many of the bodies that were unclaimed by family members and whose space wasn’t paid for, were removed and later put on display.

Some of the mummies are from the 19th century and some are as recent as from the mid-20th century. The museum shows the more “interesting” ones – often the most grotesque – and there are little descriptions, often written in first person as though the dead person is telling his or her own story.

Some bodies are wearing decayed clothing. Others are nude with wizened genitals and remnants of pubic hair. Some are grimacing. Some have injuries, like a man who died of knife wounds.

I think I was the only non-Mexican in the museum at the time. It was morbidly fascinating, but when I saw a woman extend her selfie stick to take a photo on her phone of herself beside a grim-looking corpse, I wondered where to draw the line.

On the way out, there were two wooden coffins standing up that you could step into and a sign suggested, “Live the experience. Take a photo here.”

As I walked back to the historic centre, I noticed death symbolism everywhere. There were stalls by the museum selling keychains with skulls on them. There were figures of death and La Catrina, the skull with the lady’s hat.

A clothing and fabric store had skulls in its window decorations. The main Hidalgo Market had drawings and artwork of mummies and skeletons on display. A candy store chain is called La Catrina and features her skull in its logo.

Wall posters, even children’s artwork pasted on walls featured skulls.

At two different churches, I saw festivities that I assumed to be weddings. When I asked, however, I was told they were funerals. At one, a woman was carrying a massive bunch of white balloons.

Representations of skulls and death apparently date back to pre-Columbian cultures, notably of the Aztecs, who celebrated Mictecacihuatl, the goddess of death. But the Mexican death culture also draws from European traditions, notably the Dance of Death or Danse Macabre. And it also draws heavily from traditions in Catholicism.

Catrina had her origins between 1910 and 1913, just before the Mexican Revolution, in drawings by Jose Guadalupe Posada, who was satirizing the way people at the time adopted French and European culture and denied their indigenous ancestry.

Later, she was made famous by the muralist Diego Riveira (born in Guanajuato) who included Catrina in his great mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central.

I did a lot of exploring on foot during the rest of the day, but I’ll write about that later.

I suspect I’ll have nightmares tonight.