Today I looked death in the face – literally.

Let me first explain that Mexican culture treats death very differently – on so many layers.

One of the biggest events of the year is Day of the Dead (Dia de Muertos) at the start of November when death is celebrated. It’s a time for families to come together and celebrate their relatives who have died, but it also has traditions that go far beyond Halloween.

The calavera – literally skull, but often a decorative one – is a major icon of Mexico. Walking around Guanajuato, I sometimes saw people with a calavera on their shirts, much like some people wear Che Guevara, or especially in Mexico, Frida Kahlo.

Perhaps the best known calavera is La Catrina, a skull wearing an elegant lady’s hat. More on her later.

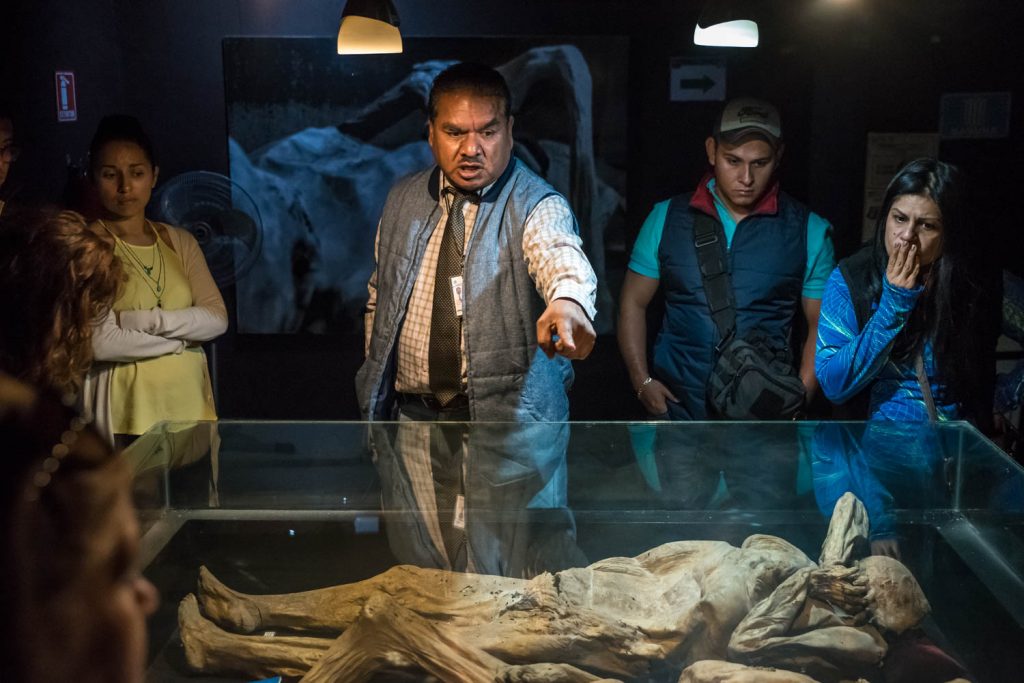

All this is to introduce the Museo de las Momias, or Mummy Museum, which I visited this morning. It’s a popular attraction, mainly for Mexican tourists, but I suspect a similar museum in Canada or the United States would be quite controversial and would probably cause outrage. As I said, attitudes about death are different in Mexican culture.

Long before the museum was established, dead people in Guanajuato were placed mainly in above-ground crypts. In the dry atmosphere, their bodies were mummified.

When the cemetery ran out of space, many of the bodies that were unclaimed by family members and whose space wasn’t paid for, were removed and later put on display.

Some of the mummies are from the 19th century and some are as recent as from the mid-20th century. The museum shows the more “interesting” ones – often the most grotesque – and there are little descriptions, often written in first person as though the dead person is telling his or her own story.

Some bodies are wearing decayed clothing. Others are nude with wizened genitals and remnants of pubic hair. Some are grimacing. Some have injuries, like a man who died of knife wounds.

I think I was the only non-Mexican in the museum at the time. It was morbidly fascinating, but when I saw a woman extend her selfie stick to take a photo on her phone of herself beside a grim-looking corpse, I wondered where to draw the line.

On the way out, there were two wooden coffins standing up that you could step into and a sign suggested, “Live the experience. Take a photo here.”

As I walked back to the historic centre, I noticed death symbolism everywhere. There were stalls by the museum selling keychains with skulls on them. There were figures of death and La Catrina, the skull with the lady’s hat.

A clothing and fabric store had skulls in its window decorations. The main Hidalgo Market had drawings and artwork of mummies and skeletons on display. A candy store chain is called La Catrina and features her skull in its logo.

Wall posters, even children’s artwork pasted on walls featured skulls.

At two different churches, I saw festivities that I assumed to be weddings. When I asked, however, I was told they were funerals. At one, a woman was carrying a massive bunch of white balloons.

Representations of skulls and death apparently date back to pre-Columbian cultures, notably of the Aztecs, who celebrated Mictecacihuatl, the goddess of death. But the Mexican death culture also draws from European traditions, notably the Dance of Death or Danse Macabre. And it also draws heavily from traditions in Catholicism.

Catrina had her origins between 1910 and 1913, just before the Mexican Revolution, in drawings by Jose Guadalupe Posada, who was satirizing the way people at the time adopted French and European culture and denied their indigenous ancestry.

Later, she was made famous by the muralist Diego Riveira (born in Guanajuato) who included Catrina in his great mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central.

I did a lot of exploring on foot during the rest of the day, but I’ll write about that later.

I suspect I’ll have nightmares tonight.