A corpse on a funeral pyre at Manikarnika Ghat was no longer recognizable as having once been human, but the smell of burning flesh was unmistakable.

My “guide” explained that parts of the cremated bodies, such as the pelvis, are not completely burned in cremation, but are put into the river with the ashes.

My “guide,” who claims not to be a guide, but rather an old Brahmin involved with showing people the cremations, said he doesn’t want money for himself – just a donation for wood that I will give to an old widow who looks after the hospice.

I didn’t mind using him as he spoke good English and knew about his subject matter, including where I could and could not go.

When we first met, he had a word of warning for me – do not take photos. I knew this was strictly prohibited, but he told me that the previous day an Israeli tourist took a photo. The angry family of the deceased attacked him, took his camera and smashed it and threw it into some flames, my “guide” claimed.

He explained to me that there are some kinds of people who are not cremated. These include sadhus, because they’ve already been purified, young children, because they are still pure and pregnant women because they have a purified child inside. Also excluded are lepers and some others.

Manikarnika is the main burning ghat where cremations take place, but there are other ghats that operate on a smaller scale. I saw a couple other corpses wrapped in cloth, waiting for their cremation, but the one I saw at the beginning was the only active cremation at that time. My “guide” told me they are conducted around the clock. He showed me areas where they can do from four up to a dozen at one time.

At the top is an area where VIPs such as politicians are cremated.

He explained how untouchables who work at the ghat will go through the ashes in search of gold jewelry and other valuables that the families leave on the bodies when they are burned.

Dying in the holy city of Varanasi and subsequent cremation by the Ganges is something many Hindus aspire to. It frees them from the cycle of reincarnation.

We now go behind the burning area and up the hill a little. Piles and piles of wood are stacked, filling a large area. My “guide” explained that different kinds of wood cost different amounts, all expensive. Most precious is sandalwood, which is too costly for most families, so they often buy just a symbolic kilo of sandalwood to burn along with other less expensive wood.

While not the most cheerful place, the burning ghat is such an important part of what Varanasi is that I wanted to experience it again.

Other than that, I spent my last morning in Varanasi exploring some of the twisting alleys between my hotel and the burning ghat. It is so easy to get disoriented as you never know what direction you’re heading and can sometimes end up going in a circle.

Then, later that afternoon, I caught a train for Bhopal, my longest train ride of the trip. It was supposed to take about 16 hours, but ended up taking several more because of delays.

My ticket had been waitlisted when I bought it, and over the weeks since mid-January I had watched my position in the queue improved so that on my day of the journey I was up to RAC status, reservation against cancellation, which gets you on the train, but doesn’t necessarily get you a birth unless someone cancels.

Two days earlier I had also bought a second class sleeper ticket on the tourist quota so that if my birth never materialized, I would have a place to lie down for this long trip. Finally, however, just a couple hours before the train left, my waitlist status changed from RAC to confirmed, meaning I would get a birth in 3 AC class as I’d originally tried to book. I was also able to get a partial refund on the inexpensive sleeper ticket, which had only cost around $5.

The trip was long with little to see in the flat Ganges Plain and it soon got dark. I was relieved when my fellow passengers agreed to turn the seat back into a middle bunk so that we would have three levels on which to stretch out and lie down. As in the other AC (air conditioned) classes, railway staff delivered clean bedding to everyone as night approached.

In my area was a family with young children who bounced around all over like little Energizer bunnies. One little germ factory was coughing and sneezing and spewing germs. I suspect he was the cause of a cold that I came down with the following day.

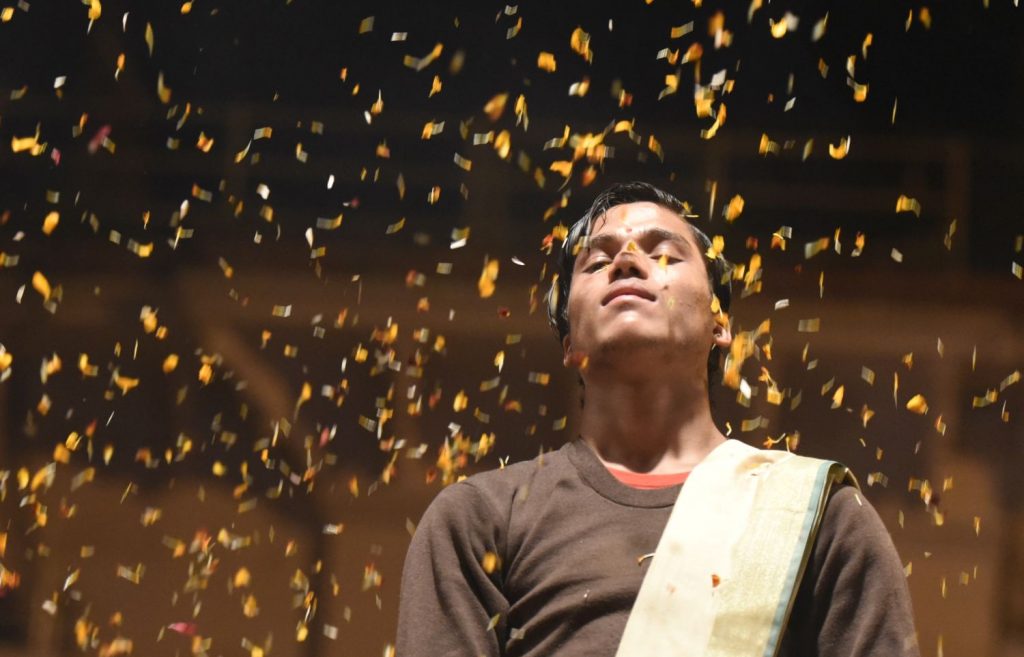

Ganges at Varanasi. (Richard McGuire photo)